The Fine Print: Why Deterrent-Based Immigration Policy Doesn’t Work

Welcome to my monthly opinion column, The Fine Print, where I will dive into a law, policy, or court case and break down how it actually affects our world today, both nationally and locally. From Supreme Court rulings to Congressional legislation, I connect the dots between legal decisions and real life. As a local high school student passionate about law and current events, I’m here to make sense of the legal world, one case at a time.

In 1996, there were approximately 5 million undocumented immigrants living in the United States. As of 2022, that number has risen to 11 million. But contrary to popular belief, this rise in undocumented immigrants permanently living in the U.S. has a lot to do with the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, commonly referred to as IIRIRA, which forever altered the core values of the U.S. immigration system. Passed in 1996 by President Clinton as part of his “prevention through deterrence” border enforcement strategy, IIRIRA was meant to deter migration to U.S. borders by strengthening immigration policy, but the practical effect was much different.

Before IIRIRA, Mexican immigrants (who make up the largest number of undocumented immigrants in the U.S.) were about 50% likely to return to Mexico within a year of arriving, lowering the number of undocumented immigrants permanently living in America at the time. As reported by Vox, undocumented immigration before the 1990s was usually temporary, as people would often move back and forth across the border to maintain family ties while also seeking job and business opportunities. If an undocumented individual residing in the U.S. wanted to live here permanently, there were legal channels available to them for achieving lawful status, such as marrying a U.S. citizen, or getting sponsored by a family member or employer.

However, IIRIRA essentially eliminated these legal avenues to lawful status with its notorious 3- and 10-year bars. After its passage in 1996, undocumented immigrants who had been living in the U.S. for 6 months to a year would be required to leave the country for 3 years before they could apply for legal status and attempt to re-enter the country. More extremely, undocumented immigrants who had been living in the U.S. for more than one year would be barred from the country for 10 years. While these bars were intended to deter undocumented migrants from entering the U.S., in reality, they prompted more people to stay in the U.S. permanently, without proper documentation, especially because the law was passed during an era of increased government spending on agents at U.S. borders. It became too dangerous to travel back and forth across borders, or to apply for legal status, as many immigrants risked being forced to leave their families and jobs in the U.S. behind for 10 years.

IIRIRA made few exceptions for these deportations, only offering “cancellation of removal” to those who had been in the U.S. for over 10 years and could demonstrate that a U.S. citizen (possibly a spouse or child) would suffer “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship” if they were deported. Family separation did not meet this standard on its own. Worse, cancellation of removal could only be granted to 3,000 immigrants per year. IIRIRA also created “expedited removal,” which allows immigration enforcement officers (rather than judges) to order deportations, essentially stripping immigrants of their right to a hearing before being removed from the country.

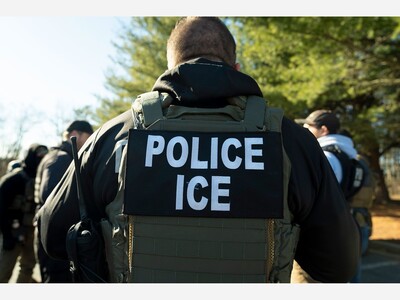

Today, the Trump administration plans to carry out mass deportations of resident undocumented immigrants. Aside from the moral and economic consequences of these mass deportations, if it weren’t for IIRIRA and the years of legal precedent building on it, the majority of the undocumented population currently living in the U.S. would already have or be eligible for legal status. Currently, it’s popular to frame undocumented immigrants as “criminals” for having “neglected” to gain documentation, but it is IIRIRA’s harsh and ineffective 3- and 10-year bars that are actually to blame.

Here in West Windsor, we are surrounded by immigrants, both documented and not. New Jersey has the fifth largest undocumented immigrant population in the country (475,000 as of 2022). They are people we know, people we go to work with, and people we go to school with. Mischaracterizing them as “illegal monsters,” as President Trump has referred to undocumented immigrants on numerous occasions, fails to account for the decades of immigration policy built on IIRIRA that are truly responsible for our large undocumented population.

IIRIRA is the prime example of why deterrent-based immigration policy doesn’t work. It hasn’t changed the reasons why people choose to enter the U.S., or stopped them from doing so—it has only made it harder (almost impossible) for undocumented people already living here to obtain legal status, forcing them to live in constant fear of deportation, without work permits and safety-net benefits that would allow them to better provide for their families and contribute to our economy. The Act has driven us to wrongly define immigrants as criminals, informing current immigration policy almost 30 years later, which has New Jersey residents preparing for ICE raids and living in fear.

To responsibly address IIRIRA’s lasting impact, we need new pathways for undocumented U.S. residents to gain legal status. Immigrants already living here without documentation (often for years) should be able to work towards citizenship without having to leave the country for a decade, an opportunity that could boost U.S. economic growth and increase quality of life for undocumented U.S. residents. West Windsor residents can help make this a reality by writing to state senators (Andy Kim and Cory Booker), House representatives (Bonnie Watson Coleman), and state legislature members in support of legislation like the Immigrant Trust Act, which would codify protections for immigrants in light of expanded deportation efforts. Making concerted efforts to move away from language like “illegal aliens” when discussing undocumented immigrants in daily conversation can also humanize how we view immigration policy. From implementing new legislation to changing perceptions of immigrants as criminals, it’s time we undo the damage inflicted by IIRIRA.